By Rev. Cameron Trimble, CEO of Convergence

“We need help forming a vision for our congregation,” the congregational leader told me. “Coming out of the pandemic, we seem lost, like we can’t figure out who we are or how to move forward,” he went on. “I don’t know how to lead us through this. I am just as disoriented as everyone else. It seems like it’s time for help.”

These are conversations we frequently have with congregational leaders at Convergence. We are living in post-normal times where it’s become difficult to fix and maintain our bearings. For many congregations, the pandemic has left them with 50% of their pre-pandemic attendance. Those who have returned are aging with less energy to give to leading programs. To top things off, this year the budgeting process was painful as giving is dropping as investment decreases. It’s not easy being in congregational leadership right now.

I’ve been working as a congregational consultant for over 20 years. I remember some years ago, around the year 2015, I was working with a number of congregations who all wanted to design their 2020 visions. I was struck by their insistence on that time period. Why did they want to dream about their future in a 5-year block? Why not 30 years? Or 2 years? Or 17 years?

I quickly discovered that it was because they liked the comfort of thinking of the future as a linear timeline of predictability. Five-year segments felt safe and memorable. The boundaries of a five-year plan still felt ambitious but didn’t risk being too far out of sync with major disruptions in the world. These leaders were trained in the art of forecasting, foresight and scenario planning. Imagination played only a limited role in so far as their imagination could be supported by data.

I also came to realize that these leaders needed a framework to declare their SMART goals and plan out their new growth strategies. They held a cognitive bias that the world of institutional religion was not on the edge of major disruption, even as all of the research suggested that we needed to pivot. While change in the world was happening at breakneck speed, change in congregations could (and should) be at a slower pace. They gave themselves permission to ignore clear signs on the horizon that change was upon us, though we did talk a great deal about “God doing a new thing.”

In those years, it was also still believable that we could make educated guesses about the world in 5 years, so planning still felt possible. We had a sense that technology was changing, well, everything, but congregations still felt that they could keep following orders of worship from the 1800s, and balance their budgets through giving in the Sunday morning offering plate.

I realize now that leaders were under tremendous pressure to “have answers” to the problems of the present that would be solved by a “plan” for the future. They couldn’t afford to account for disruptive forces in their communities because it was hard enough to address the challenges of the moment. They couldn’t afford strategic imagination that might be wrong, or risks that might not work out. So, we planned in 5-year segments. We designed very tactical plans. Almost all of them lacked any sense of real vision.

Then, I got tired of being a part of that conspiracy of certainty. I recognized that strategic planning as a practice was insufficient for leading congregations, organizations, or businesses into any meaningful future. I began searching for a more creative way to dream about the future of our congregations and a more honest process for making that vision possible.

A Poverty of Imagination

The fallacy of our planning processes is that they assume predictability and foresight. It’s an “A+B=C” kind of process. Strategic planning approaches rely mostly on experiences from our past to inform our best guesses of the future. We were trying to imagine our future mostly by looking backward. We had a strong bias toward data and a fear of uncertainty. This created a poverty of imagination evidenced in our outcomes. We couldn’t think beyond what we had experienced or what we heard others had experienced (in the past). In this way, we were doomed to stay stuck in limited thinking.

Of course, institutional religion was not alone in this challenge. Working with companies and NOGs, I saw the same pattern. I remember working with a publisher who refused to consider the impact that Amazon would have on their book sales. I worked with a team at an international business corporation that couldn’t account for a collapse in their B to B (business to business) sales model that was transitioning to a B to C (business to consumer) model for their competitors. They couldn’t imagine a future where their way of doing things wouldn’t work as it had in the past with a few tweaks.

As I began studying more approaches to visioning work, I spotted a limitation in my own thinking. While most of my clients held an image in their minds of a linear process of A+B=C, I held an image of a labyrinth. My sense of the work was going out and coming in, going out and coming in. Each pass taught us something new and expanded our vision. But it assumed ONE path, with new insights along the way.

Thinking Like a Futurist

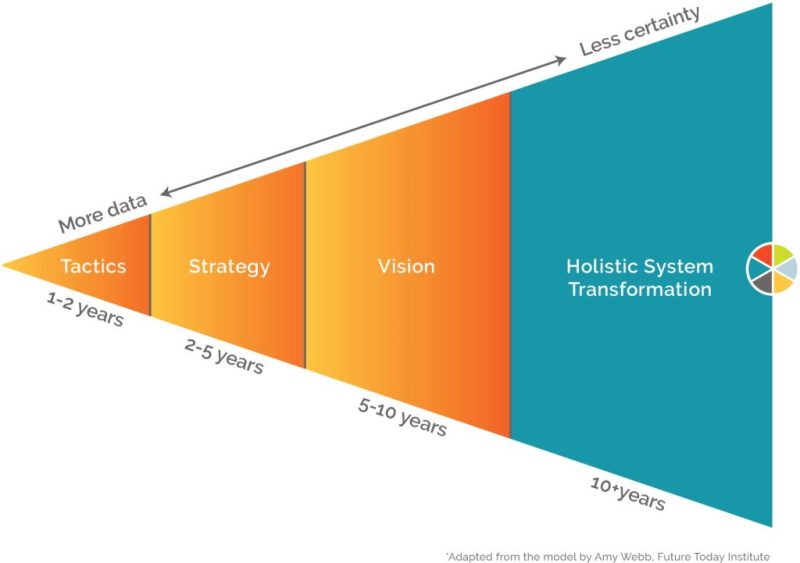

It wasn’t until I encountered colleagues working in Futuring that I began to understand my own limited thinking. When you think like a futurist, your relationship with time changes. You don’t think in terms of linear time. Instead, you think in terms of your proximity to certainty. Amy Webb, the founder of Future Today Institute, offers an effective visual to illustrate the shift. I’ve adapted her model to fit our context.

When I began to think of visioning and forecasting as a cone of proximity rather than a line of predictability, I understood the power of this thinking for religious institutions.

For so many years, congregations designed strategic plans rich in tactics loosely tied to strategy. But they were missing the connection to the holistic system transformation and therefore limited in our ability to create meaningful impact in our communities. They simply couldn’t see at that level of emergence complexity.

Most strategic plans of congregations came out looking something like this:

Years 1-2

- Hire or fire the senior leader

- Redo the bylaws

- Update the database

- Rent out the building

Years 3-5

- Develop/expand mission to serve homeless

- Expand small groups

- Strengthen congregational care

- Right size the staff

Years 6-10

- Wrestle with financial sustainability

- Network with other congregations (since denominations will be smaller)

- Figure out what to do with our building (for real this time)

- Strengthen small groups

These are all fine things to do. But do you read that list and feel hope for the future? Do you have a sense of the difference any of those steps will make for the transformation of the world? These steps are disconnected from the disruptive realities of modern life.

Over in Europe, a group of scholars and educators with UNESCO were developing a complementary approach to futuring work called Futures Literacy (FL). FL is a leadership capability that empowers individuals and communities to imagine, anticipate and then negotiate multiple possible futures. Each of these futures holds different possibilities. Each of them can teach us something about the kind of world we wish to create.

Here is what I mean: you and I have a story about the future that we tell ourselves every day. We have a “future world” in our minds that we are betting on. In truth, we have a few stories that we tell ourselves. When I am worried about the economy, I might tell myself that my future investment portfolio is in jeopardy, so today I need to be conservative with my spending and saving. But tomorrow, I might hear or read something that makes me feel encouraged about the economy. So my story might shift to “Everything is going to be ok! I can keep going on my current path.” Both of these stories may be true. We can’t predict the future. But they impact my actions TODAY. They also teach me something about the present that might be useful to architecting the future: I want to be financially comfortable regardless of the state of the economy.

Many congregations today tell themselves stories about their future. They tell a story about decline in attendance and giving that will only increase in the future. They tell a story of why families with young children left the congregation and why they will or won’t come back. Their story often assumes that families with young children are the solution to their present problems. These stories shape how we see the present, and how we invest our time, talent and resources now.

Making conscious these stories that we tell ourselves about the futures we are betting on then gives us the power to act creatively rather than be reactive to impacts or beholden to the strategies designed by those who have historically had the resources and power to colonize the future.

The tech industry has stories about the future. The banking industry has stories they tell about the future. Multinational companies have stories they tell about the future. Nation-states have stories they tell about the future. How do your stories align or diverge? If you don’t have an answer to that, you risk being colonized by theirs.

At this point, the scale of visions in our congregations matters so much. Congregations are intermediaries of community resilience and transformation. We advocate for values and resources that serve the common good. Our failure to imagine futures where communities advocate for individuals and protect the vulnerable means we will fail in our primary mission as people following the way of Love. Our dreaming too small in the future means we act too timidly in the present. We are irrelevant before we even start.

Our great need today is leaders who develop within themselves the imaginal muscles of futures literacy. We need leaders who look at our probable future (with all of its heartbreak and hope), imagine desirable futures (with all of their possibility and risk), and work for breakthroughs in service to a more just and generous future for everyone.

Your Congregation as a Futures Lab

Today I spend much of my time leading congregations and denominations through Futures Labs where we play with this imaginal capability. We wrestle with the creative possibilities that exist within our stories of our probable futures and our desirable futures.

I was working with congregations in Newcastle, England recently. Together, we imagined that we were in the year 2070. I asked them to describe the world they would bet on. What is their sense of the probable world in 2070? Here is what they said:

- We will have less access to energy

- There will be a bigger gap between the rich and the poor

- Our communities will be more intergenerational with more people aging and living at home longer

- Climate change will be THE great issue of the time

- Climate change will result in global conflicts and war as people groups fight for access to resources

- A primary tension in communities and nation-states will be around migration

- We will not have a cash-based economy; we will have adopted a different economic model

- There will be less land because of rising sea levels; in fact, Newcastle may not even exist

- Because of collective trauma and grief, society will be more accepting of talking about mental health issues and a need for mental health support

- People will live longer and be in better health

- We will have created solutions for fairer resource distribution

- We will be more diverse with more people being of mixed race

- We will see a return to the more traditional skills of farming and caring for the land

- We will no longer use fossil fuels.

On the whole, they discovered that they were mostly optimistic about the future. The stories they were telling themselves about the future included many positive evolutions even while acknowledging the challenge of climate change.

I then asked them what they thought religious gatherings would be like in the year 2070. Here is what they said:

- Denominations will be gone. What remains will be more dynamic and responsive to the yearnings of the age.

- Congregations will be smaller, and we will have fewer of them. Instead, we will meet in homes, and more intimate spaces.

- Our practices and activities will be simplified – back to the basics.

- Hybrid connection will remain important – we will connect in-person and through technology.

- Our sense of spirituality and connection to the Sacred will be stronger.

- More people will have access to “mega-congregation” experiences online which may breed extremism.

- The role of buildings will shift to community centers and hubs used every day of the week.

- The religious landscape will hold a variety of beliefs and be more interfaith and ecumenical in spirit.

- We will serve people at the margins.

- We will have new music to sing and design new liturgies to meet the realities of the day.

- The world will be even more secular and we will feel the impact of the growing influence of China and India.

- Congregations will embody a closer connection to creation, reclaiming some of the teachings of previous generations.

Can you begin to see some of the assumptions that this group is holding about the future? They are assuming that people will still meet in congregations. They are assuming that we will still have buildings. They are assuming that people will stay in the area long enough to establish some consistency of gathering. They are assuming that mega-congregations will still be an attractor for large groups.

These assumptions are all underneath their thinking, unarticulated until we push farther into the Futures Lab process.

I then asked the group to think about their desirable future. They spoke of beautiful things such as wanting to see children engaged in the big questions and mysteries of life; structures that are less hierarchical and have more fluidity; people are more loving and kind by being in community with one another; diversity is embraced and inclusion is valued; and congregations are places that pursue the deep mystery, awe and wonder of God.

The Reframe

I then generated a scenario designed to undermine their assumptions. If they assumed we would have buildings, I imagined a world where buildings didn’t have value. If they assumed that people would stay in the community for much of their lives, I created a scenario that required migration. In other words, I reframed their assumptions into a world that pushed their imaginations even further.

Here is what I said: “It’s the year 2070. Climate change has killed nearly 6 billion people on the earth. People now move frequently because of social and climate disruptions. Most institutions have ended, including schools and denominations. What does spirituality and/or institutional religion look like?

There was silence in the room as they processed this new possible future. It wasn’t a probable or desirable future. It wasn’t right or wrong. It was simply a future that would push their imaginations in new directions. Here is what they discerned:

- Daily practices of faith and prayer are essential in a world encased in deep grief over climate change and social disruption;

- Our practices, values and theology will be even more grounded in nature;

- How our communities will be led is a question that will need to constantly evolve;

- Grief will be omnipresent and we will need rituals and stories of hope to ground us;

- Our sense of connection will also define our sense of safety. Being in a “group” may mean the difference between life and death;

- Big questions become important to address: What is the meaning of life? What is the meaning of MY life? How do we learn about love? How do I become wiser?

- Joy matters. Gratitude matters. Play matters. Celebration matters. As survivors of a world ravaged by climate and violence, we must give thanks for what remains;

- Our sense of place is more fluid. The congregation is anywhere two or more are gathered;

- Community and belonging are tied to people we know rather than neighborhoods or congregations;

- In some ways this would be a blessed restart for religion – an invitation back to the basics of a simpler way of life and a simpler, less formal faith;

- Worship would happen in all kinds of places and in all kinds of ways.

As they wrestled with the possibilities of this reframed world, their true values began to surface – community, spiritual depth, compassion, care for the earth, and celebration. In a reframed world, they want to embody ways of being grounded in these values. They want to create practices that support these outcomes. They want to invest in relationships and institutions that work for this story of the future world.

Coming Back to the Present

We turned then from our future visioning to the strategy cone, asking, “What steps could and should we take today that create the field of emergence for the future we could see?” In other words, together we have stories of the future that we want to create. What steps do we take in the present to make them so?

Designing strategies for the congregation’s actions today suddenly had new meaning. Something valuable was at stake in their success. They had a future they dreamed of together and felt called to bring into reality for the generations to come.

In deeper reflection, they began to see patterns, blindspots, assumptions, challenges and opportunities for their church. They realized they could not make the following assumptions about the future:

They cannot assume…

- Capitalism is a sustainable economic model. They want to be part of creating a better way to measure and trade what they value.

- Communities will be stronger. They commit to ministries that support belonging, inclusion, and personal growth.

- Communities will be weaker. They will be a ‘School of Love’ where they teach the practices of peace.

- Denominations will save us, hold our identity, or justify our existence. They treasure their covenantal connection and will work to live out the values that they share in common.

- Equality is likely in the future. Therefore, they wish to invest in a future where all people are treated with dignity and have enough.

- Crisis only creates negative change. They will ready themselves to embrace opportunities to make our communities, nation, and world a more just and generous place.

- People will live here as long as they have in the past. They sense that people will move at a greater rate so we will invest in building structures accessible both near and far.

- All people will live on earth. If some people live somewhere other than earth, then they have a new and more expansive label to adopt as “earthlings.” This may be the key to growing our sense of global connection and inviting deeper collaboration.

With these insights in mind, they came to a deeper understanding of the role and function of congregations:

- Congregations are “Schools of Love” where people come to learn about love, grace, peace, wisdom, compassion, and community. They are not competing for customers on a Sunday morning. Instead, they are a network of friends seeking to follow the way of Love.

- Institutional congregational life is declining in scale and may not be the primary (or only) way of living out our identity in the future. This is an opportunity to work collaboratively with organizations of like vision, mission, and values. “Saving our building” cannot be the primary mission. Our mission is to ‘be with’ the community.

- Clean energy and interdependent living are honored and rewarded. As our institutions deconstruct, we will rebuild more sustainable models going forward.

- Those who are vulnerable through poverty, migration, violence, and oppression can and should find safety and opportunity through our efforts. We must support efforts near and far to level the playfield of inequality.

Finally…

For most of religious institutional history we have used:

Planning (for optimization)

- Based on repetition, data and statistics

- Based on past experiences, unique to the individual

Preparation (for contingency)

- Innovation within closed systems, rapid development, goal-oriented

- Self-improvement, individual learning, goal-oriented

Futures Literacy adds a third leadership capability:

Exploration (for emergence)

- Complexity and uncertainty are embedded in decision-making

- Being present, individually letting go of expectations; more journey, less destination

It’s a new capability for most of us in leadership today. It’s a powerful practice in imagining a world that works better for everyone. It may very well be our best tool in saving our planet.

To learn more about hosting a Futures Lab for your congregation, contact us at Convergence. We would love to work with you.

Rev. Cameron Trimble is a serial entrepreneur committed to the triple bottom line – a concern for people, peace, and the planet. Driven by an adventurous spirit, she runs businesses and NGO organizations, both secular and faith-based. She serves as a consultant, a frequent speaker on national and international speaking circuits, is a pastor, pilot and an author of numerous books on leadership.

Contact Cameron at cameron@convergenceus.org or follow her at camerontrimble.com.